Toronto’s neighbourhoods are notorious for their low-density typologies and their high cost of housing. Yet, their impact extends beyond their property lines and limits the design and density of nearby mid-rise and tall buildings on main streets and major transit lines. This might seem illogical for a city in desperate need of more housing supply, but it’s not an unintentional side effect that limits potential mid-rise and tall buildings. It’s an everyday planning tool that is ubiquitous in Toronto’s design policies. It’s angular planes.

What Are Angular Planes and Why Does the City Enforce Them?

Angular planes are outlined in many of Toronto’s design guidelines. They apply to most, if not all mid-rise and tall building development applications across the city. But what are they?

Picture an imaginary 45-degree angle barrier that acts as a “cut-off” for how deep and tall a building can be. They can apply at both the front and rear of a property. The angular plane can start at different points on a property depending on variables, like the size of the lot or type and location of nearby properties, but the key is that the new building cannot protrude through the imaginary angular plane. This is why you’ll often see mid-rise buildings with large deep floors towards the bottom but floors with step-backs towards the top.

That’s the quick and easy way to describe angular planes, but if you want the technical description, here it is.

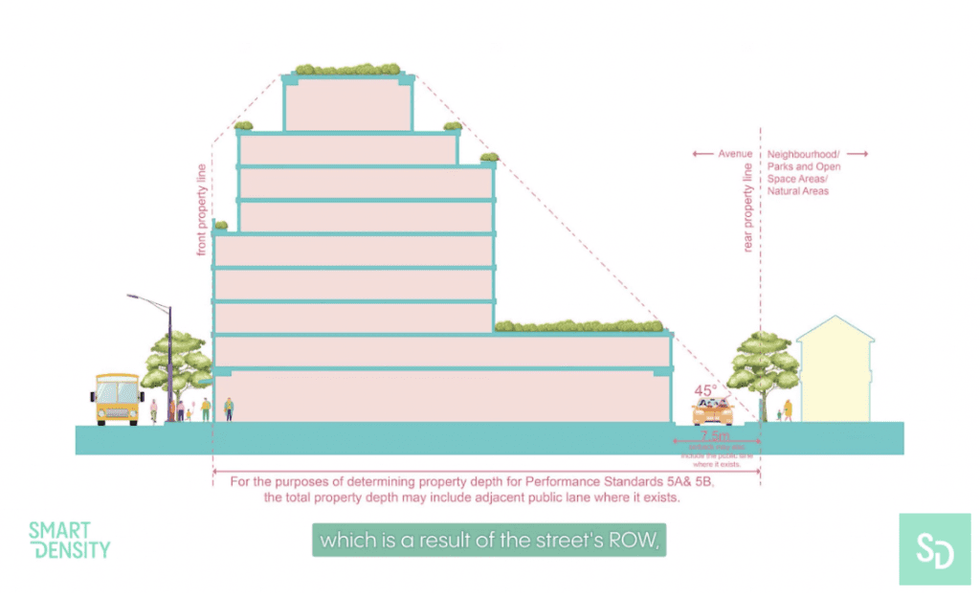

As per Toronto’s guidelines for mid-rise buildings on avenues, the maximum height of a mid-rise building is equal to the distance between the property line on one side of the street to the property line on the opposite side. This is also known as the right-of-way.

To figure out the angular plane in the front of a property, imagine a line that extends upward from the front property line, all the way up to 80% of the right-of-way distance. That’s where the 45-degree angular plane begins and starts cutting off upper floor square footage. It’s similar in the rear, except the angular plane begins 7.5 metres in from the back property line or from the edge of the adjacent laneway (if there is one) and up either 7.5 metres or 10.5 metres (depending on whether or not the lot is shallow).

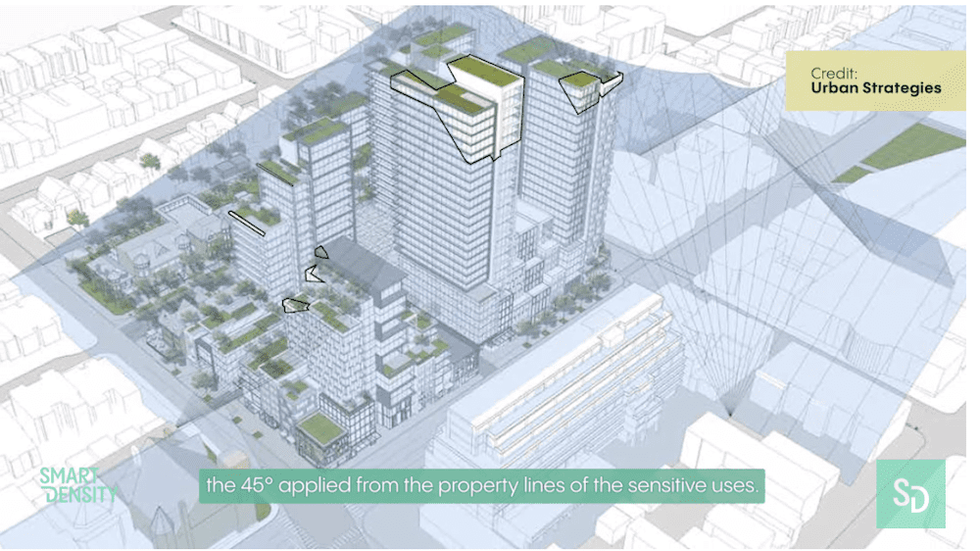

Angular planes for tall buildings are similar and encourage height transitions from tall buildings down to nearby lower-scale buildings and areas, including stable residential neighbourhoods and open spaces. The angular plane extends on a 45-degree line drawn from the property lines of these more sensitive areas, limiting the maximum height wherever the plane reaches the tall building.

READ: Ontario Needs More Supply. But Slashing Planning Rules is Too Steep a Price

Still with me? If you have more questions about angular planes, I recommend checking out the City’s design guidelines for tall buildings and mid-rise buildings. I also recently created an online course, “Planning for Non-Planners,” that explains angular planes and other essential planning concepts through bite-sized videos and easy-to-understand terms.

Unlike the technical details, the City’s intent for the angular plane policy is simple: to protect the public realm from buildings that cast massive shadows all day long and to create consistent transitions from low- to mid- to high-rise buildings. And they have done exactly this. They’ve also helped to create a diverse skyline with towers of all shapes and sizes and have helped communicate to developers an “appropriate” height for new buildings.

The Hidden Costs of Angular Planes

Although the reduction of shadows, diversification of the skyline, and appropriate heights can be beneficial to the city, it all comes at a cost. Affordability has been an increasing issue for Torontonians over the past decade, and the demand continues to rise for housing relief especially in the downtown region. Angular planes result in lost square footage -- square footage that could have been additional homes.

Angular plane policies send a strong message. They suggest that the backyards of those who can afford to live in single-family dwellings in the heart of Toronto are to be prioritized over the countless Torontonians who can’t afford housing because of low supply.

It is well known that the most sustainable and efficient way for our cities to move forward is by increasing density and moving away from the car dependent, low-density sprawl that has contributed to the housing crisis in the first place. While the construction of low-density housing is not a City priority, existing low-density housing remains the centerpiece that new development has to build around. Angular planes decrease a city’s ability to move past an urban typology where low-rise is the norm, and transition to a high-rise environment because it assumes that all current single-detached homes will remain single-detached homes.

Angular planes also add complexity to the development process since they require top floors to have different, smaller layouts than those below. This is more complicated because the floor configuration has to change significantly at each level. Different floor plates make it harder to achieve higher density because the design and construction teams cannot reuse floor layouts in higher floors. With each floor having a unique layout, it also makes vertical duct runs and mechanical stacking next to impossible, which increases complexity and cost.

Combine this additional cost with the potential square footage cut out by angular planes and it becomes very clear why angular planes are a housing affordability issue.

Focusing Beyond Single-Detached Homes

The angular planes imposed on mid-rise and tall developments are a result of the prioritization placed on single-detached homes with large front yards and backyards for families to play. But it doesn’t need to be like that. We can think of parks as our communal front yards and backyards. We can stop fixating on the excuse that new taller buildings will greatly reduce direct light -- this is especially nonsensical since in the winter months, the sun is so low that low-rise neighbourhoods are already in the dark for most of the day. We can start to think of single-detached homes as underused private space that should be densified.

We could scrap the concept of angular planes altogether. They protect properties in Toronto that the City knows are not a recipe for future success. Overall, angular planes in their current state are a benefit to some and a cost for most. They force architects and developers to build less for more, and are in need of an update.