The provincial government made a flurry of announcements over the past few months, and one of the new pieces of legislation that could come to have the largest impact on both developers and residents involves transit-oriented development.

Bill 47, the Housing Statutes (Transit-Oriented Areas) Amendment Act, was first announced on November 8, with the Province designating transit hubs around BC as transit-oriented development areas and establishing minimum heights and density requirements.

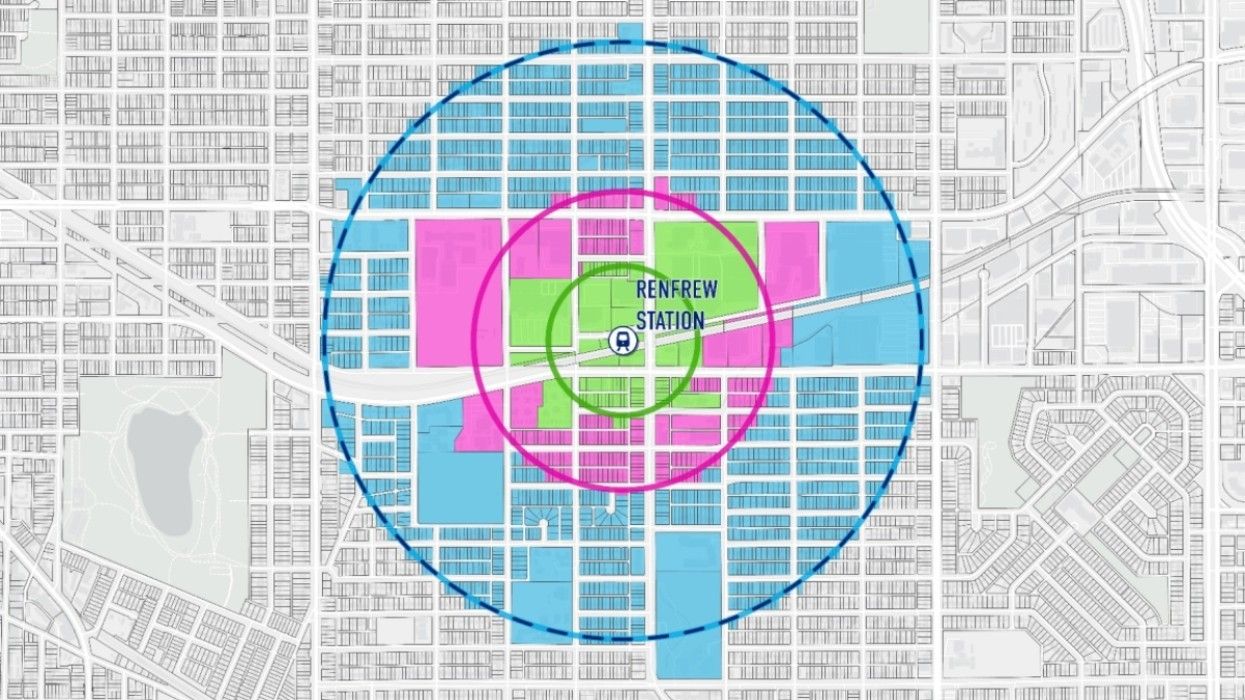

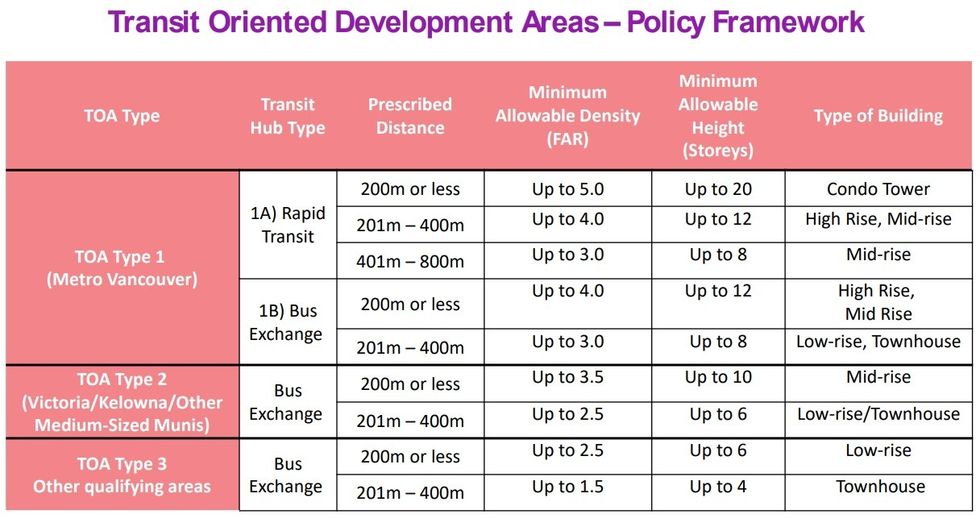

Those transit-oriented development areas will consist of two types: those within 800 m of a SkyTrain station and those within 400 m of a bus exchange (with variations for municipalities outside of the Metro Vancouver region) with minimum heights and densities steadily decreasing for sites further away from transit hubs.

In Metro Vancouver, the highest minimum density and height will be an floor space ratio of 5.0 and a height of 20 storeys for sites within 200 m of a rapid transit hub — a SkyTrain station — and decrease to a minimum of 3.0 FSR and eight storeys for sites between 201 m and 400 m away from a bus exchange.

No further details were provided by the Province, with the Ministry of Housing saying more specifics about the policy would be released in December. That came earlier this month, on December 7, but many in the industry who have reviewed the policy manual believe that many of their questions about the legislation have still not been answered.

President of Darwin Properties Jason Turcotte says the various pieces of legislation the Province has announced were "bold," but that the transit-oriented development legislation was the biggest miss.

"With not requiring municipalities to pre-zone, in my mind, all you've done now is guide some future planning work. By not mandating the pre-zone, you're basically going to be left with a situation where the municipalities that were already doing a good job of densifying around transit will continue to do so and those that aren't now have no greater impetus to do it better than before."

Under the legislation, Turcotte points out, municipal governments cannot reject development proposals in transit-oriented development areas on the basis of height or density, but they can still reject them on any other basis. Because the Province's legislation does not change the rezoning, there is still a lot of room for municipal governments to get around it and reject transit-oriented projects, if they want to.

"By not mandating what the density is, by way of a pre-zone, what you're saying now is 'Okay, municipalities, you have to allow someone to rezone a site next to transit for, let's say, 12 storeys and 4.0 FSR, but you can put any other obligation or condition that you want on that rezoning. It could mean that you provide 4.0 FSR of housing and half of it has to be non-market. Well, that's a non-viable development. [City's can say] that if you're not prepared to do that, then they have no obligation to approve it, or they could find some other reason. There's just no obligation. It's a really bold move on the surface, but it's actually toothless in changing the behaviour of municipalities that were not already doing a good job of it."

Ian Brackett, Senior Broker at Goodman Commercial, adds that the legislation also does not prescribe uses and tenures, such as whether housing has to be strata or rental, nor does it outline the definitions of affordability and below-market housing.

"That being said, other legislation introduced requires municipalities to more regularly update community plans and to pre-zone properties to conform with those community plans, so over time, the TOD framework will likely be reflected in actual changes to zoning laws," said Brackett.

Michael Geller, an adjunct professor at SFU and real estate consultant, has concerns that are more on the practical level. He's currently working on a project, as a consultant, that's planned for 27th Avenue and Cambie, and has been going back and forth with City staff over some fine details about the project. The staff have been "difficult," he says.

"Then along comes this provincial document that says this particular location warrants a building that's eight storeys, not six storeys, and a floor space ratio of up to 4.0, rather than 2.5," Geller says. "So here's a real practical dilemma for my clients. Do we continue as we have been and try to resolve the minor details of the building, or do we put down our tools, wait a year, and hope that we can get a significantly higher density? Now, that's an isolated situation, but it's going to be happening all over the province."

Geller says he thinks the team that put together the legislation did a good job of identifying the opportunities, and he commends their work, but he suspects that they did not sit down with municipal planners to figure out whether the physical services of those transit-oriented development areas can really support the higher level of development, not to mention other related aspects such as school capacity and community centres.

Asked how he thinks the various new pieces of legislation the Province has announced in recent months may intersect and interact with one another, Geller says he's curious to see what happens if there are any sites that are subject to the small-scale multi-unit housing legislation as well as a transit-oriented development area.

"I have to admit, on one hand, it's quite exciting. On the other hand, I worry that some of it is too aggressive. If the government is not careful, what could easily happen is some of these developments might proceed, and the public will react negatively, and then we might find ourselves with a new government coming in — the Liberals and/or Conservatives — that actually rescinds many of these planning directives. I don't think that's out of the question."

- BC Gov Announces Transit-Oriented Development Project In Port Moody ›

- PCI President Tim Grant On The Ins And Outs Of Transit-Oriented Development ›

- BC Is Allowing Up To Six Units Per Lot. Will They Actually Be Built? ›

- How Much Money BC's 188 Cities Are Getting To Implement New Housing Legislations ›

- BC United Releases Housing Platform Ahead Of 2024 Election ›

- How Major Municipalities Are Handling BC's New Housing Legislations ›

- Vancouver Outlines Housing Requirements In New TOA Rezoning Policy ›

- Feds Push For Transit-Oriented Development With $30B Canada Public Transit Fund ›