In a city like Toronto, where housing demand chronically swells well past the supply available to accommodate it, affordable housing can too often feel like a footnote to the larger conversation. But for Abigail Bond, it’s front and centre.

Bond joined the City as Executive Director of the Housing Secretariat in February 2020, at something of a critical juncture. At the time, Toronto had just approved its HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan, which was calling for the creation of 40,000 affordable rental and supportive homes. Bond had the tall order of carrying it out. A daunting task, sure, but Bond tells STOREYS she was motivated by the challenge. Prior to joining the City of Toronto, she had spent nine years as Managing Director of the City of Vancouver’s homelessness services and affordable housing programs and found she had a real interest in that line of work.

After spending the next five years with the City of Toronto, Bond moved on from her role this past Friday. We spoke to her on her last day at City Hall about the landscape of affordable housing in Toronto, and the advice she has for her successor.

STOREYS: What led you to join the Housing Secretariat back in 2020?

Abi Bond: I was working at the City of Vancouver doing housing and homelessness work, enjoy[ing] it immensely, and saw this opportunity at the City of Toronto, which was to implement their 10-year plan. And municipalities across the country have these 10-year plans, but the opportunity to do that work at one of the largest municipal governments in the country when they were at the very start of that journey was really attractive. At the time I remember thinking, there's a lot of ambition; this new HousingTO 10-year plan, it's like a North Star they've created on housing and I would love to work there and help implement it.

S: What were your main goals when you started?

AB: I was interested in understanding what was in the 10-year plan. So thinking about homes for people experiencing homelessness — what were we going to do about that; middle-income earners — people were coming to the city, new households were being created, and if the average person was no longer able to afford to buy here, what were going to be the alternatives; and market rental housing — all different kinds of affordable and rental housing, what could the City do around that. And then how can we deliver on that? I knew we had to take these plans and strategies and make them real.

The other thing was the creation of the Housing Secretariat itself. Because the 10-year plan is a North Star document, you need a group within the City to really champion and drive that. The Housing Secretariat, when I came to the city, was around 15 people — a very talented group of people, but very, very small. In fact, the team was smaller than the team I left at the City of Vancouver, and it's obviously a much smaller city compared to the City of Toronto. So over the five years I've been here, the team has really grown, and that was one of my goals.

S: What did you take from your time with the City of Vancouver that you brought to the City of Toronto?

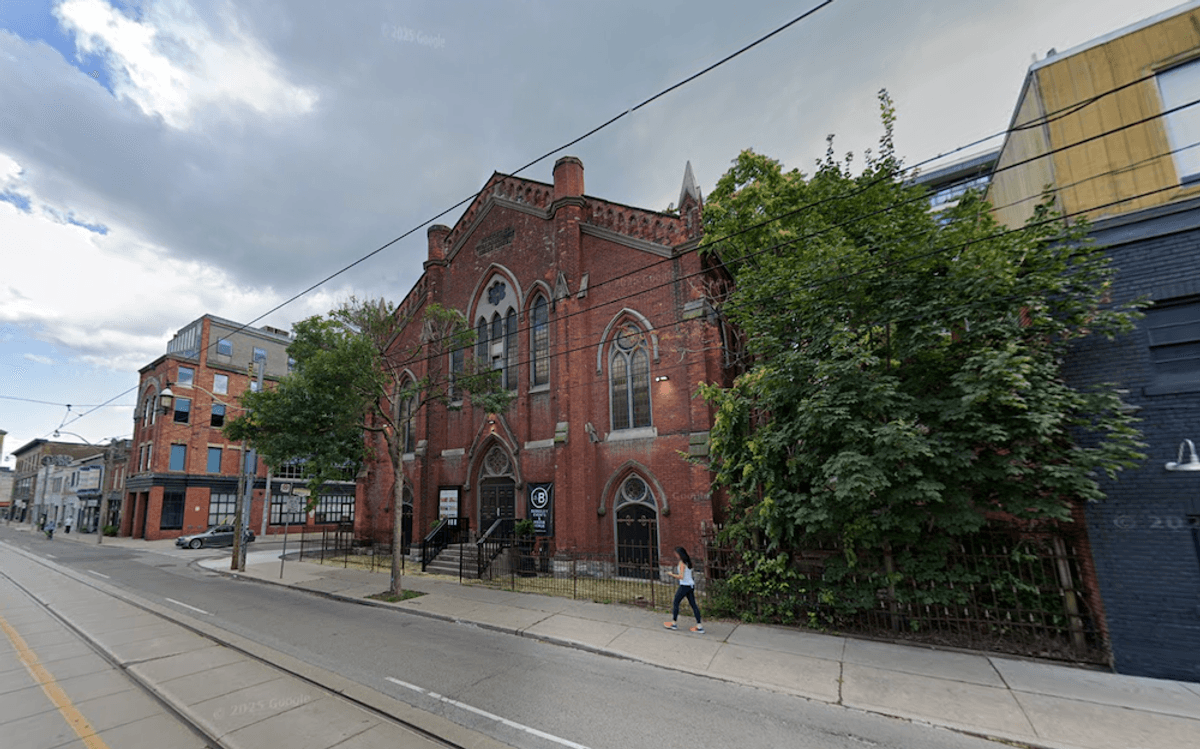

AB: I had had some success at the City of Vancouver in doing a rapid deployment, rapid building for people experiencing homelessness. In Vancouver, we did that as temporary modular housing. Here, there was an interest in doing something more permanent, but again, using City land and using different types of construction to make things go faster. So that was a real focus for me when I first came. The other thing that was similar — we saw it in Vancouver, we're seeing it here now — was a real resurgence in the idea of co-op housing. As I was leaving the City of Vancouver, there was interest from the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, and then here, there’s the Riverdale Co-op, and also one of Housing Now's sites, 2444 Eglinton, which is one of the largest new co-ops in the country.

S: What are your thoughts on the work of CreateTO and the Housing Now initiative?

AB: The program is ambitious. It has tried to deliver thousands of units and really hit a number of key obstacles around interest rates, labor disruption, pandemic, supply chain — so costs for all those deals started to go up, and that made it really difficult for the proponents to stick to what their original concepts were. So the City has had to be flexible, we've had to work with those partners, and it's taken some time to make sure they can get their financing and funding. What we're learning we're rolling into other sites we're doing with CreateTO, like some of the public builder sites and other sites we're bringing to market. So none of that work is lost, and those sites will continue to move forward. And you can see some of the learnings and the fruits of that in the new Toronto Builds report. It’s an attempt to take the learning from all the programs and think about what's next, what's the future, and how can we continue to build out those sites and add more.

S: In 2022, you put out a report that discussed ending vacancy decontrol. Talk to us about that and other protections you think are missing from the rental market.

AB: We were asking the provincial government to consider vacancy decontrol and the effect that it has in the market. But that wasn't the real focus of that report, it was a much larger report and my approach was for government to think more holistically about the problem. You do, as a government, have to think carefully about how you use your policy levers. For us at the City of Toronto, that's been things like legalizing multi-tenant homes, renovictions, as well as building new rental. And for me, it was about trying to get, certainly the provincial government, who has maybe the largest role to play in the world of rental and how that shows up in the city, to think more holistically about what it is that we need to do to improve the situation for renters. Vacancy decontrol is one aspect to that. It's one which could really stabilize rent for existing renters. It may also have the effect on dampening supply.

So these are not easy policy conversations, and I think they're best had with community and levels of government and trying to find a way to a new future where being a renter is accepted; you're not in a financially disadvantaged position, you've got choice about where in the city to rent, and you've got some protection around the legislation that governs you. All of these things could, in the end, support our economy, because stabilizing rental housing is about stabilizing the homes that key workers in our city live in.

S: What are your hopes for the new renoviction bylaw, and what are your concerns about its rollout this summer?

AB: I'm very optimistic about its rollout and I think it's really going to be a game-changer for renters. It will put them in a stronger position of knowledge around what their rights are and how they can exercise their rights. What I would say is, there is a very delicate dance that has to be done between the rights of tenants and their responsibilities and those of landlords. And what we don't want to do is create a situation where we make it too hard for landlords to want to rent out their properties. And so that balance is really at the heart of a careful and intentional rollout of that program. Communication will be everything; making sure tenants and renters understand and also helping landlords to understand will be really important.

S: How has the landscape of affordable housing, and the City's relationship with it, changed since you joined the Housing Secretariat five years ago?

AB: I would say the biggest change has been turning ambition into confidence. The City was ambitious when I came — it had this new 10-year plan — but there was not a lot of confidence that we could really do everything. It was a huge ask. It's a comprehensive plan, 72 actions, that deals with every aspect of the housing ecosystem. What I would say now is the City is confident in its ability to respond to the housing crisis and to go above and beyond what is normal for a municipality. We can build the partnerships with the other levels of government, we can go it alone if we need to. The City now has a momentum and an energy around its ability to deliver, which was not necessarily there when I joined. Not to the degree that it is now.

S: What sorts of attributes do you hope the next Executive Director of the Housing Secretariat will have, and do you have any advice for them?

AB: Housing progress is not always linear or a straight line. It can feel a little chaotic, a little messy. And so having people working at the Housing Secretariat and in leadership who understand that and use that to create the energy to move forward is really important. It's not always easy to find the way, and yet, because of the success we've had, there's a lot of opportunity. The one piece of advice I would leave is that creating new [housing] is great, but we also have to think that that new home is going to be here for the next 100 years, and we have to make sure that we have the systems in place to look after it, to make sure people can access it equitably, that there will be reinvestment in those homes, that we won't lose them through a lack of reinvestment. So, thinking about not just what you have in front of you, but the next 100 years, is important. And the Housing Secretariat team, anyone who's lucky enough to come in and lead them, you have the best group. They're energetic, they're motivated, they're resilient, they love this work, and they're deeply committed to it.

S: Do you have any plans to return to the City of Vancouver?

AB: It's one of those things — I can neither confirm nor deny. I really can't say anything about what I’m doing next. It's probably the most common question I've been asked, and I will be able to say very soon. I'm very excited about it and it's going to be a real privilege to do this next role, and I look forward to being able to tell everyone.

Questions and answers have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

- Gregg Lintern Has Advice For Toronto’s Next Chief Planner: ‘Have Humility’ ›

- For Toronto’s New Chief Planner, City Building Is A “Team Sport” ›

- A Q&A With Valesa Faria, Executive Director Of Toronto’s New Development Review Division ›

- Toronto's New Renoviction Bylaw Goes Into Effect Today ›

- Toronto Launches New Housing Development Office: Q&A With Jag Sharma ›