Despite moves that have been made on the gentle density front over the past few years, Toronto is notorious for having restrictive zoning policies that rarely budge, with the lion’s share of its land zoned for single-family homes and not much else. As far as Smart Density Founder Naama Blonder is concerned, zoning policy as it stands today translates to a missed opportunity when it comes to housing.

A gargantuan one.

Blonder — an architect and urban planner, with an ear to the ground when it comes to city building — says that a pervasive narrative she’s hearing all too frequently is that Toronto is “maxed out” when it comes to housing. In a recent article posted to the Smart Density website, she described Toronto being perceived as “full and dense,” with “no space left for growth.”

“I've been hearing it quite often, to be honest, even from industry leaders, even from university profs — just too often, trust me. [They’re saying] ‘we are dense enough, it's time for us to direct the growth to smaller municipalities, and all of that,’” Blonder tells STOREYS. “But you look at Toronto and you see the amount of single-family houses, so I wanted to explore how much room we actually have.”

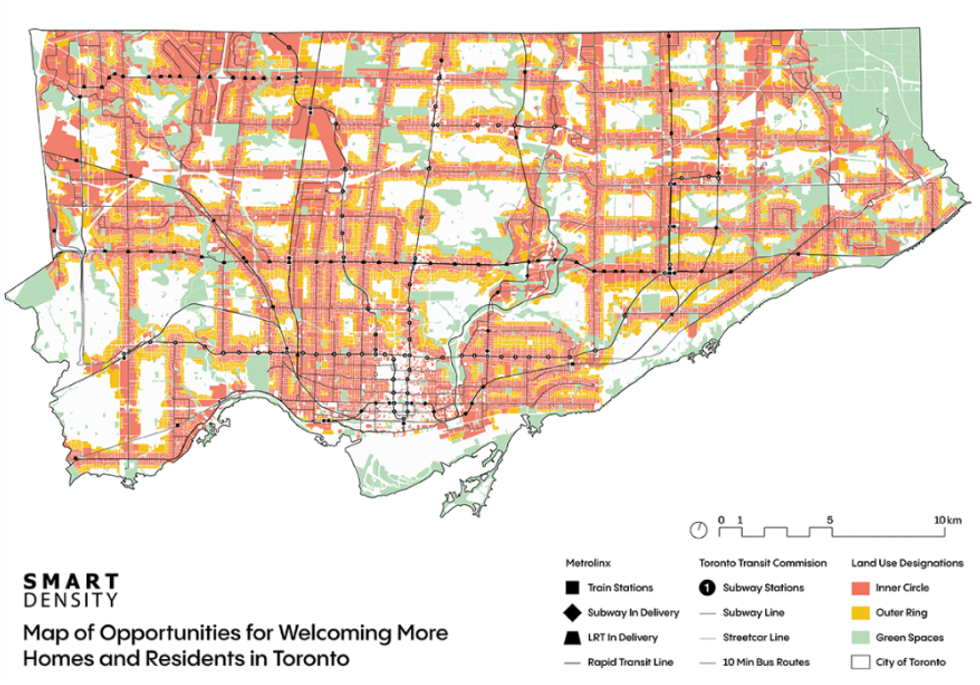

Blonder tasked her team at Smart Density with finding out exactly that: how much of Toronto is residentially developable, but also transit-oriented. Her argument is that Toronto stands to make better use of its existing transit — think: TTC stops, streetcar lines, 10-minute bus routes, and more — as well as its future transit options like the forthcoming Eglinton Crosstown LRT.

Here’s what they found.

Toronto, hypothetically, has the potential to accommodate a whopping 7.6 million new homes and 12 million new residents near transit “without compromising quality of life.” This was surmised using data from Ratio.City which is a division of Esri Canada, and minds a ‘conservative’ estimate that 30% of land would not be developable.

“We said that, okay, from all the under-utilized land that has room to develop, part of it will be heritage, or part of it will be owners that don't ever want to sell, or part of it will be facing a ravine and have some constraints on it,” Blonder notes, when speaking to how her team reached that 30% figure.

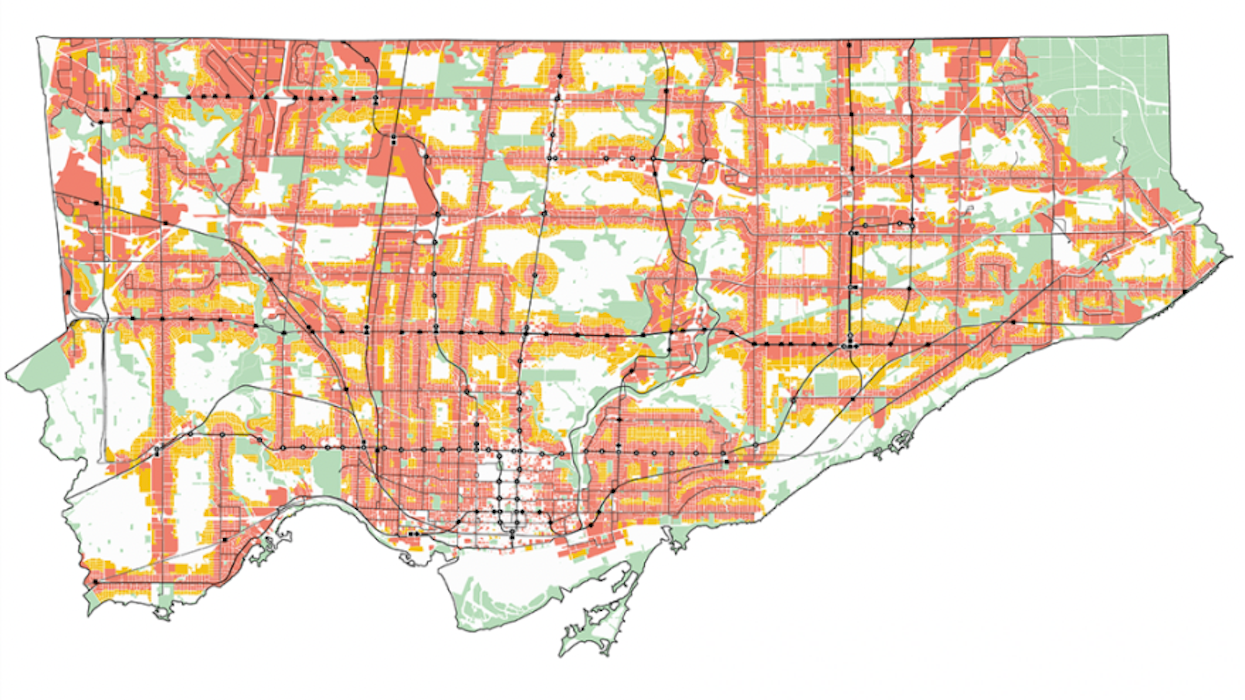

Smart Density’s findings on the matter are nuanced, mind you. In the above map, four key colours are shown, including the “inner circle” in orange, which represents areas closest to transit areas (within 400 to 800 metres of rapid transit and 250 to 400 metres of frequent transit), and the “outer ring” in yellow, which represents areas that are not immediately proximate to transit, but still suitable for residential development.

“We decided to focus on transit because that's where we see the most potential for policy change. And it makes the most sense, especially around parking and car usage,” Blonder explains.

More broadly, she emphasizes that Toronto is need of radical change when it comes to zoning. Recent moves to encourage gentle density are in the right direction, but she maintains that it’s not nearly enough given the way the city is growing, and the way housing affordability has been whittled down to near non-existence.

“We really need to focus our efforts near transit. One of the models we [considered] was Glencairn station. You get out of the subway, and there's nothing there. It's just single-family houses all over,” she says, adding that the same can be said about “almost any station” in the Danforth area.

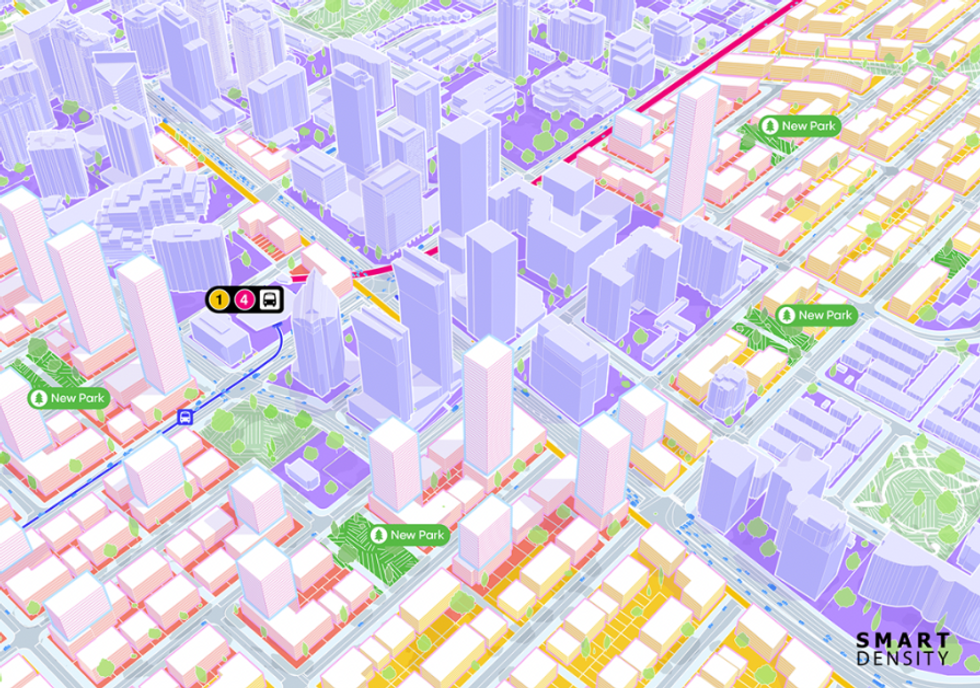

“And you will see in our models, we didn't [include] any hyper, hyper density. That's really an important point,” Blonder also notes. “We accounted for the Toronto that we want to see, with much larger average unit sizes and much more average open space per unit. The towers there are 20, 30 storeys tall. Not that I'm saying there's no room for taller — absolutely, there's demand — but we also accounted for four, six storeys, just to show the type of variety and definitely move away from the single-family model.”

The aforementioned article from Smart Density’s website touches on the urgency of the matter, underscoring that without planning policy reform in some capacity, Toronto is bound to see a “massive displacement and a city affordable only to the wealthy.”

As for whether or not ridding the city of its restrictive zoning policies is realistic, Blonder argues it’s just common sense. “Near transit that cost us billions of dollars you have single-family houses, like, how does that make sense?” she says. “I'm not suggesting [that we] welcome, tomorrow morning, 12 million people. I'm saying that for those who think that we're ‘maxed out,’ here are the numbers to prove that we are far, far away from that.”