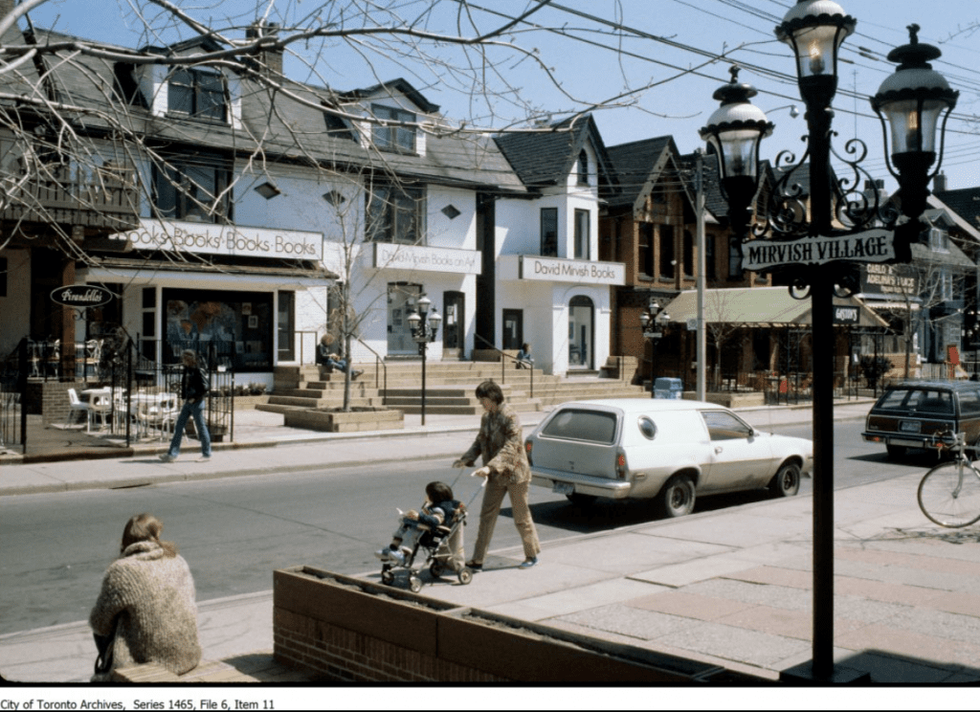

Markham Street runs north-south for 3km, from Follis Avenue to Queen Street West, showcasing an array of architectural styles as it passes through Toronto neighbourhoods like Seaton Village and Palmerston-Little Italy. Its most popular stretch has been the roughly 200m run from Bloor Street West to Lennox Street in Mirvish Village, lined with shops and bars in former Victorian homes. Today, the village is closed as the houses go through restoration as part of Westbank's Mirvish Village redevelopment.

Mirvish Village has seen notable figures dining and schmoozing, while the neighbouring Palmerston Boulevard to the west housed some of the city’s wealthiest people, including former Toronto mayors and the Weston family.

While Markham Street south of Lennox may not have had as many notable names living on or visiting it, one address did house a budding athlete who in 1928 travelled to Amsterdam with five other women for the historic opportunity to represent Canada at the Olympics.

An All-Around Athlete

Born in 1904 in what is now Ukraine, Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld was the second of five children. The family came to Canada and settled in Barrie a year after her birth. In 1922, they moved to Toronto, settling on the northwest corner Markham Street and Herrick Street. Rosenfeld attended Harbord Collegiate Institute in 1923 and got the nickname Bobbie for her bobbed hair.

Rosenfeld’s athletic talent was noticed at a young age. It didn’t matter if she played basketball, hockey, softball, lacrosse or tennis because she had a record of carrying herself and the teams she played on to title wins and championships across Canada.

Her entry to track and field was unconventional. Rosenfeld attended a picnic tournament with her softball team who encouraged her to compete in the 100-yard race. Rosenfeld entered the competition, which was also being run by Canada’s top sprinter Rosa Grosse. Rosenfeld, unaware of Grosse, shocked spectators as she beat the country’s top sprinter and claimed a Canadian record in the sport.

This win earned her invite to train with Grosse and other female runners, and eventually to head across the Atlantic Ocean to the Netherlands to be part of an Olympic first.

The Matchless Six

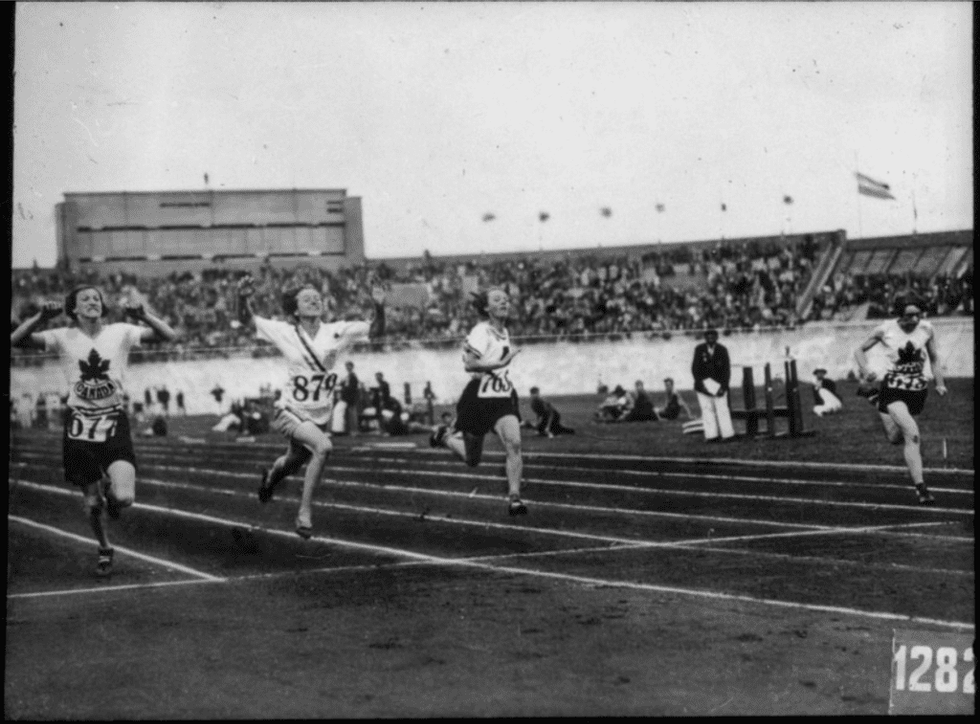

At the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, women’s track and gymnastics was introduced. Rosenfeld, along with Jean Thompson, Ethel Catherwood, Florence Jane Bell, Myrtle Cook, and Ethel Smith went to Europe to represent Canada in numerous track events including the 4x100m relay, 100m, 800m, high jump, and discus. The six women became known as the Matchless Six.

Rosenfeld attended the games and participated in the 100m, 4x100m relay and 800m. While she intended to compete in discus, a scheduling issue arose when she qualified for the 100m final held at the same time. She chose to run the 100m race where she earned a silver medal. The race was so close between her and American runner Betty Robinson it sparked debate among spectators, judges, and athletes as to who actually won.

Rosenfeld was the starting runner in the 4x100m relay race with Ethel Smith, Myrtle Cook and Florence Jane Bell. The four women had never competed as team before the Olympics, but went on to shatter a world record with a time of 48.4 seconds as they took took home the gold medal.

She also entered the 800m at the last minute to support her teammate Jean Thompson. Many describe her actions in the race as an example of good sportsmanship, as Rosenfeld could have easily won bronze but chose to run beside Thompson who had fallen, letting her finish fourth while she placed fifth.

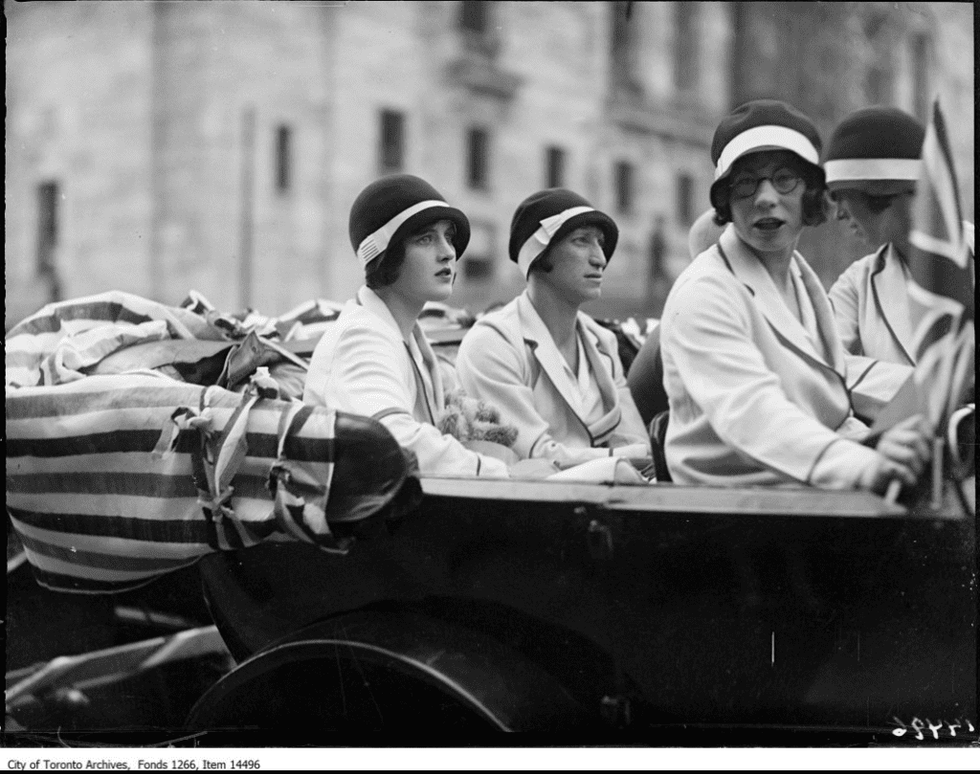

When the women returned home a parade was held with over 200,000 people in attendance. Sadly, Rosenfeld’s post-Olympic career was plagued with medical issues as she was diagnosed with arthritis a year later, leaving her bed ridden for eight months and on crutches for a year. She eventually played sports again, but her condition ended her sporting career in 1933.

After retiring from competition, Rosenfeld kept working in the sports field through coaching and writing. She became a journalist, spending three decades with The Globe and Mail where she wrote a column called Sports Reel and ran the promotions department. In her column, Rosenfeld promoted women’s sports and fought sexism as some critics claimed athletic activity made women unfeminine.

Living on the Corner of Herrick and Markham

When the Rosenfeld family moved to Toronto in 1922, they settled at 496 Markham Street next to Palmerston Boulevard. While Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld eventually moved, her family lived at the property until 1951 before it was converted into apartments.

The streetscape is relatively the same from that time, though the trees are a little taller, some of the homes are showing their age and the house directly across from the former Rosenfeld residence was recently built. The Rosenfeld family predated Mirvish Village and it wasn’t until after they moved that Ed Mirvish began buying the properties on the 200m stretch of Markham Street. However, they would have been around for the opening of Honest Ed’s.

The home is over a hundred years old. It is a three-floor Edwardian structure with discoloured bricks and a number of bay windows on the front and side, some donning stained glass and others covered with vines. The tree on the front lawn drapes over the home covering most of the second and third-floor façade, but leaves a clear view of the large deep covered veranda with columns and a low bannister.

The interior of the home, like many in the area, was retrofitted for apartments. The current occupants, an elderly couple, said there is hardly anything original from the Rosenfeld era and jokingly noted when they moved in they found bathrooms in places you wouldn’t expect. While there isn’t much left of Rosenfeld’s time at the home, her legacy is still remembered across the country.

A Legacy that Keeps Running

Rosenfeld died in 1969 and was buried at Lambton Mills Cemetery in Etobicoke where her gravestone features the Olympic rings, cauldron, and flame. Her name is a mainstay in Canadian sports with the Canadian Press’ Bobbie Rosenfeld Award given annually to the top Canadian athlete of the year. Superstars Christine Sinclair, Bianca Andreescu, Penny Oleksiak, and Eugenie Bouchard have all been recipients.

Rosenfeld was named Canada’s Female Athlete of the First-Half of the 20th Century, achieved Canadian and world records, was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame, and has a park named after her in Toronto nestled within the Rogers Centre, CN Tower, and Ripley’s Aquarium. She was also shortlisted for the Canadian $10 bill, which now features historic Canadian civil rights activist Viola Desmond.

The couple living at 496 Markham Street were smiling when I chatted with them about Rosenfeld’s home. They knew she lived at the property as they’ve been visited by sports enthusiasts and historians over the years. They also want to honour her legacy and told me their goal is to have a plaque erected on their front lawn so pedestrians can learn about Rosenfeld’s extraordinary life and career.

Hopefully that happens before the 100th anniversary of her landmark silver medal in Amsterdam.