Joe Berridge bailed on Toronto in the 60s.

He came to Toronto, didn't like it, travelled around Central America, ran out of money in New York, and then accepted a job — sheepishly, he admits — at the University of Toronto.

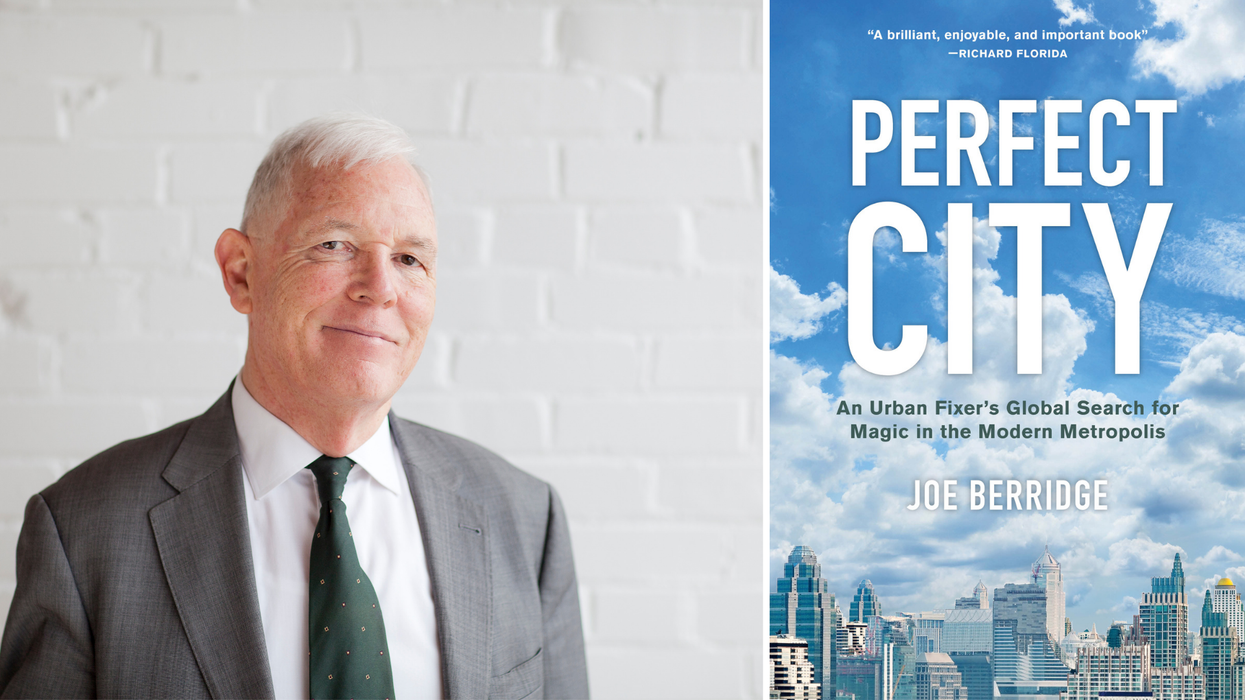

So he came back and started a life here, including a decades-long career in city planning, currently as a partner in the firm Urban Strategies. Berridge just published his first book, Perfect City: An Urban Fixer's Global Search for Magic in the Modern Metropolis, and as fate would have it, Toronto now regularly cracks Top 10 lists of global cities.

We recently chatted with Berridge about the city’s superpower, how Torontonians continuously underrate ourselves, and why Toronto is finally interesting enough to keep its global pop stars.

One of the most fascinating parts of this book is between Singapore and Toronto — you point out that they are the only two cities that rose out of relative obscurity to the global stage in the last century. Yet they accomplish that in completely different ways: Toronto by accident, Singapore in a very deliberate, engineered way. How is that possible?

That’s the wonder of the urban world. (laughs)

It’s fascinating and it’s what I find so intriguing. I have to say that most of the cities I work in, that I mention in the book, are very, very deliberate about advancing their global status. They promote themselves very aggressively and strut themselves on the world stage. And Toronto absolutely doesn’t, in comparison. And yet it’s the accidental winner.

What it made me think was: what is it that drives city success? It’s certainly isn’t PR. It is more fundamental things. And in Toronto’s case, it is immigration. The fact that we take so many immigrants and the quality of the immigrant flow is so high.

I love Toronto and I’m a foreigner. I think it actually takes people from outside to appreciate what’s being done here.

Whereas Singapore has a kind of utter determination not to be swamped by these enormous neighbours. It’s actually a form of self-preservation — to toot your horn loudly and be as wealthy and successful as you can — because it’s a tiny little place.

In Toronto, ’76 was around the time it gained a larger population than Montreal. Arguably, up until that point, it was a ‘nowhere town’ — yet just another midwest city like Cleveland or Minneapolis. Substantial places but not a place of global import.

So, was it disorienting to watch that happen? From 1976 to now?

I don’t think disorienting, I think it’s kind of wonderful.

I also think it has provided the opportunity for generations of people who previously would have moved away. The Torontonian population of New York or Los Angeles or London is actually pretty high. But it’s all of the previous generations — people don’t go [to New York or Los Angeles] now, they stay here. Much to the betterment of the city.

I give the example of Drake. What the hell is Drake doing in Toronto? No, seriously, why isn’t he in Los Angeles? Because Joni Mitchell is, and Neil Young is. That whole generation moved out. Now they stay, and it’s wonderful.

I love the part in the book about Toronto’s self-image — being underrated. It’s something I’ve noticed among my peers and younger colleagues — lots of people don’t seem to like Toronto. And I was born someplace else but I love it here. So why is Toronto so under-appreciated by Torontonians themselves?

I love Toronto and I’m a foreigner. I think it actually takes people from outside to appreciate what’s being done here.

If you came from — and I’m guessing from your surname, the part of the world you came from — you know what it’s like to live in a peaceful city. And I come from a country that is now having a nervous breakdown.

READ: Torontonians Love Where They Live, According To Study

And so many people come here from the turmoil from the rest of the world — Syrians or the Vietnamese or the Hungarians in the 50s — that they really loved the quiet life this city can give you.

And oddly it’s the ying of the yang, the fact that Torontonians — and Canadians in general, but Toronto specifically — don’t strut their stuff, don’t toot their horn, don’t tell everybody how fantastic they are, makes it actually a very comfortable and sweet place to live.

It is extraordinary that my students — who have gone through the high school system here and in the rest of Canada — have no idea that we have the seventh most significant financial centre in the world. They go, (feigning shock) ‘What?’

Our banks didn’t do really stupid things. Every other bank in the world did really stupid things.

You use the word ‘world class’ here and everyone laughs. I can show you the publication materials of the Greater London Authority or New York City; they use the word ‘world class’ unaccented, they use it straight — ‘We want to be world class.’ New York was worried it wasn’t world class in tech employment. London was worried it was losing its world class edge in fine art.

It’s kind of sweet, in a way, that Toronto feels that way about itself.

I’ve got a two-parter for you: What’s one thing you would change about Toronto right now? And what’s one thing that you hope would stay the same?

We have to have an all-powerful, regional transit authority. That’s the first thing.

And I would also change the [expletive] weather. (laughs)

It is 6 degrees and it’s been raining for days.

I was in Ottawa yesterday and it was warm and sunny, OK? And I come back to this. I mean, goddammit, what is going on?

The Weather Network said it was warmer in February than it is now.

It’s the original sin.

But we can’t change that — so, transit.

That’s the first one. We are filling up. We are growing faster than anybody else and we really have the transit system of a city a quarter of our size.

We have just got to build very aggressively, manage very creatively, and we have got to fund from our deep pockets — which we’ve got, because we’re a wealthy place. And it takes a lot to build transit.

READ: Toronto Needs A Better Subway System, Not Nicer Stations

We are absolutely headed for a total congealing — not congestion — which is already beginning to happen. You can feel it not so much in the central city but certainly in the suburban edge. It’s really getting bad.

And one thing I would not change about Toronto — its gentle self-deprecation.

Sitting down to write this book, did anything surprise you? Did you learn anything new? Or was it mostly an excavation of your career and experiences?

The issue that you’ve [brought up] is what surprised me, while I’ve been writing it.

Toronto is securing a position in the Champions League — really only since 2008, and the idea of the book was germinating with me in the last decade or so. Even I hadn’t quite appreciated how significantly the collapse of the financial economy in the rest of the world did not happen here.

And what’s so fascinating, that sort of gentle self-deprecation and that kind of innate, small-C conservatism is why it didn’t happen here. Our banks didn’t do really stupid things. Every other bank in the world did really stupid things.

READ: Poor Little Rich City: How Much Longer Can Toronto Afford Austerity?

And the reason why we didn’t do these stupid things is that kind of conservative, Scotch-Irish, put-a-penny-in-a-shoebox view of the world. While I was working in Belfast, [I realized] every mayor of Toronto until Nathan Phillips basically came out of the Belfast tradition.

[Editors note: Berridge’s book asserts that Toronto’s reticence and unassuming demeanour was influenced by waves of Irish and Scottish immigrants, who ascended in political and financial spheres.]

It was interesting doing that excavation. But it was also working in other cities. You see a city when it just gets in the groove — like New York did under Bloomberg — it’s just a thing of beauty. It’s so impressive what a well-organized city government can do.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.